FRESCO

Fresco is a technique involving paint applied to wet or dry plaster.

Fresco involves paint applied to wet or dry plaster.

Fresco is the act of applying the paint to the prepared plaster surface, and it is also the term for the finished artwork.

Fresco

Fresco is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid wet lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting becomes an integral part of the wall. The word fresco is derived from the Italian adjective fresco meaning "fresh". The fresco technique has been employed since antiquity and is closely associated with Italian Renaissance painting.

The earliest known frescos come from the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt (2613-2498 BCE) in and around North Africa. Frescos have also been discovered that date to 2000 BCE by the Minoans during the Bronze Age of Crete.

Technique

A “true” fresco is the most durable fresco technique and consists of three coats of a specially prepared plaster, sand, and sometimes marble dust troweled onto a wall. Each of the first two rough coats is applied and then allowed to set (dry and harden). In the meantime, the artist, who has made a full-scale cartoon (preparatory drawing) of the image that they intends to paint, transfers the outlines of the design onto the wall from a tracing made of the cartoon. The final, smooth coat (intonaco) of plaster is then troweled onto as much of the wall as can be painted in one session. The boundaries of this area are confined carefully along contour lines, so that the edges, or joints, of each successive section of fresh plastering are imperceptible. The tracing is then held against the fresh intonaco and lined up carefully with the connecting sections of painted wall, and its pertinent contours and interior lines are traced onto the fresh plaster; this faint but accurate drawing serves as a guide for painting the image in colour.

A correctly prepared intonaco will hold its moisture for many hours. When the painter dilutes his colours with water and applies them with brushstrokes to the plaster, the colours are imbibed into the surface, and as the wall dries and sets, the pigment particles become bound or cemented along with the lime and sand particles. This gives the colours great permanence and resistance to aging, since they become a part of the wall surface, rather than a superimposed layer of paint on it. The medium of fresco makes great demands on a painter’s technical skill, since he must work fast while the plaster is wet but cannot correct mistakes by overpainting. This must be done on a fresh coat of plaster.

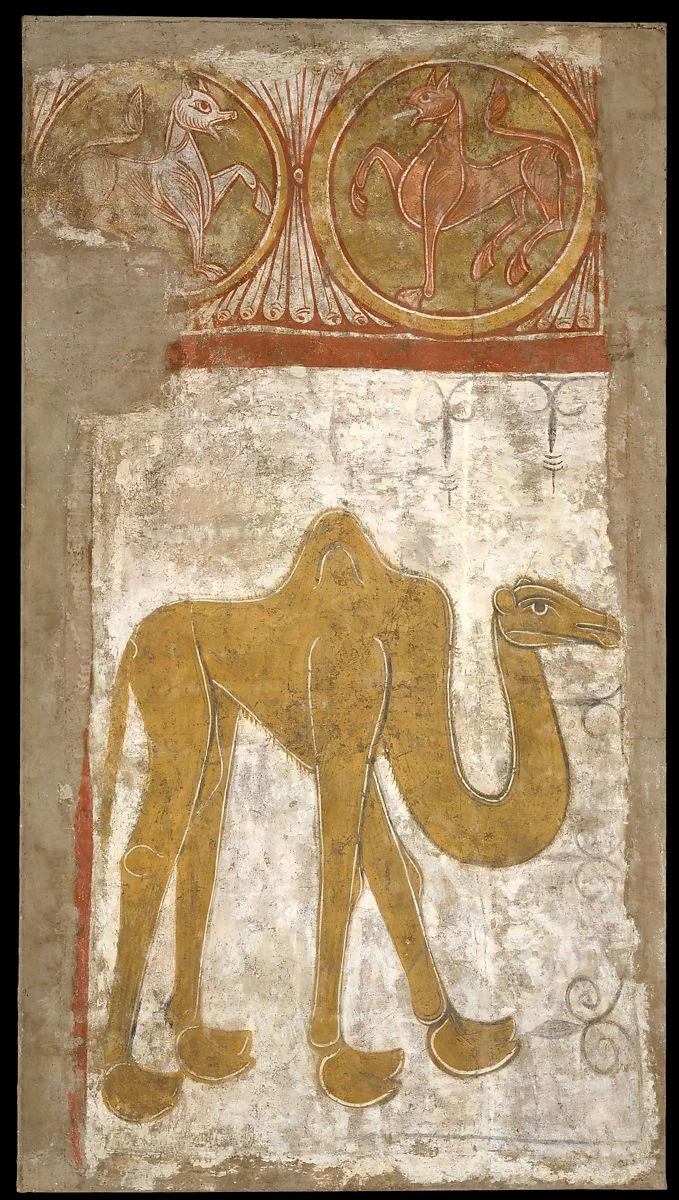

Camel. First half 12th century (possibly 1129–34). Fresco transferred to canvas. Spanish. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ward, Gerald W. R., ed. (2008). The GroveEncyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. Oxford University Press. pp. 223–5. ISBN 978-0-19-531391-8.

https://www.britannica.com/art/fresco-painting