MOTION

the changing occupation of space over time, by a physical or abstract entity

Motion

Motion is the changing occupation of space over time, by a physical or abstract entity. Motion may stand alone, as in a scene where characters are moving, such as ‘the horses are galloping around the track’, or motion may be relative to the viewer, as in ‘a bicycle is moving toward us.’

Descriptions of motion reference concepts such as stillness, quaking, rocking, rolling, hovering and more.

Adjectives describing motion deal with speed and levels of surprise such as fast, slow, jerky, or smooth.

In the mind of an artist, motion can be an element used to help the viewer comprehend a concept. Artists include perceived and suggested motion in kinetic sculptures. Time-based media artists working in video, film and cinematography utilize the motion of not only what is captured with the camera, but the movement of the camera itself to provide a 4th dimension of creativity.

Click the link below to watch a short video on Eadweard Muybridge’s Photographs of Motion.

Time, Space, Motion

Art exists in time as well as space. Time implies change and movement; movement implies the passage of time. Movement and time, whether actual or an illusion, are crucial elements in art although we may not often be aware of it.

An art work may incorporate actual motion; that is, the artwork itself moves in some way. Or it may incorporate the illusion or suggestion of implied motion.

Actual Motion

Artworks that incorporate actual movement are called kinetic. An artwork can move on its own in several ways: through natural properties or effects such as air currents, or it may be mechanically or technologically driven, or it may involve either the artist or the viewer moving it.

Using nature to move

Art that employs the effect of natural properties, either its own inherent properties or their effect, can be unpredictable. Spatial relationships within the work change continuously, with multiple possibilities. One of the delights of experiencing such artwork is the element of change and surprise. Every time we look at the art, we are seeing a new work.

Click the link below to watch a short video on the kinetic works of Theo Jansen.

Mechanical or technologically driven

This movement may be more predictable and limited than movement through natural properties, or it can seem endless, depending on the complexity of the system that moves the artwork. The motor or movement system may be purposely revealed or it may be hidden, depending on the effect the artist desires. The movement can be very mechanical, robotic, or seamless and flowing.

Click the link below to watch a short video on Chinese artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s work “Can’t Help Myself” at the 58th International Art Exhibition in Venice.

Implied motion

Implied motion is the suggestion of movement in a static work of art. Movement can be suggested visually in a work of art in a variety of ways - through the use of diagonal lines, gestural lines, and directional lines; through repetition, position, and the size of objects in the work; through the position or eyeline of a figure; or through a symbolic representation of movement.

Cropping

When an image is cropped it can cause the viewer to infer motion in a scene. Showing half of a figure or a shape that extends off the page or canvas tells the viewer there is more than what they are seeing.

Motion as an art movement.

The Futurist movement of the early 20th century embraced the idea of a technological future and glorified themes such as speed, industry, the car, airplanes, and modern cities. The Futurists’ work symbolized a sense of forward progress, speed, and determination in moving toward something.

There are many elements in the sculpture “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space,1913, by Umberto Boccioni that imply movement - the use of diagonals, the exaggerated length of the figure's stride, a sense of strong wind blowing what can be read as the figure's clothing, and the forward focus of the head.

Although the eyes of the figure cannot be discerned, there is an implied eye line that suggests the figure looking ahead, implying movement of the figure toward whatever is "seen" in the distance. An ironic emphasis is added by the use of what appear to be heavy immovable blocks from which the figure is springing.

Click the link below to watch a short video on Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe.

Motion as a subject

In the late 1940s, Jackson Pollock developed a form of painting by pouring, dripping, and splashing paint onto large canvases placed on the floor. Pollock emphasized the expressive power of the artist’s gestures when conducting the paintings. He would move and dance around the work using fluid enamel paints and sometimes and plumb bob to record his movement.

Click the link below to watch Jackson Pollock narrate his artistic process while creating one of his famous action paintings.

Optical Art

Optical art or Op art for short is a style of visual art that uses optical illusions for compositions. The works are usually abstract and typically give the viewer an impression of movement.

Op art is a perceptual experience related to how vision functions within our eyes. It creates a dynamic visual art that stems from a discordant figure-ground relationship.

Artists create op art in two primary ways. The first, best known method, is to create effects through pattern and line. Often these paintings are black and white and their relationship with one another causes the viewer to perceive them as moving. The other reaction that can occur is that areas create after-images of certain colors due to how the retina receives and processes light. As Goethe demonstrates in his treatise Theory of Colours, 1810, at the edge where light and dark meet, color arises because lightness and darkness are the two central properties in the creation of color in our eyes.

Click the link below to watch a short video detailing the intentions of optical artists.

Things to notice

- Notice if the work suggests a sense of motion.

- Are there repeated depictions of the same character?

- Are there processions?

- Is there a cropped composition or unstable poses?

- Do you see an optical illusion?

- Does the work physically move?

- If the work suggests motion what does this contribute to the meaning of the work?

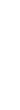

Eadweard Muybridge. Animal Locomotion, Plate 758. ce. 1887. Collotype, from "Animal Locomotion". England. Art Institute Chicago.

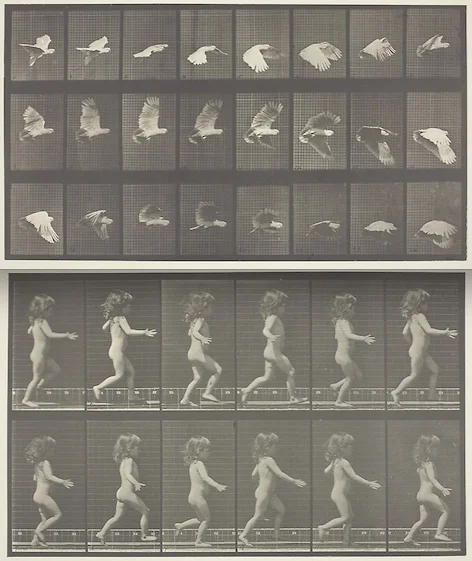

Eadweard Muybridge. Animal Locomotion, Plate 469. ce. 1887. Collotype, from "Animal Locomotive". England. Art Institute Chicago.

Clock. ca. 1852. rass, free-blown colorless and opaque white glass. American. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Katsushika Hokusai. 冨嶽三十六景 隅田川関屋の里 Sekiya Village on the Sumida River (Sumidagawa Sekiya no sato), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei). ca. 1830–32. Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper. Japan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Edgar Degas. The Dance Class. ce. 1874. Oil on canvas. French. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Umberto Boccioni. Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. ce. 1913, cast 1950. Bronze. Italy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jackson Pollock. Greyed Rainbow. ce. 1953. Oil on linen. American. Art Institute Chicago.

Victor Vasarely. VEGA III. ce. 1957–59. Oil on canvas. Hungary. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Yves Klein with Harry Shunk, János Kender. Leap into the Void. ce. 1960. Gelatin silver print. French. Museum of Modern Art. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photograph: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles